Which of these two photos do you prefer?

“Spencer corset 1941 before after” by Haabet2003, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the early 1940s when this ad campaign was created, it was probably a no-brainer to choose the picture on the right . Or maybe you would still choose that one? I’m not quite sure.

Sometimes I wonder, have corsets ever fully disappeared from women’s lives? Or have they just turned invisible, from physical to psychological corsets, in which we desperately try to squeeze ourselves with dieting, exercise and belly sucking.

Most of my life, I wore clothes that were too small for me. As a student, I had a tiny 58cm waist, and liked to emphasise it in the way I dressed. I remember my excitement when I discovered vintage high-waisted dresses from my mum’s college days in my grandma’s old closet. I’d hold my breath pulling up their tight zips. And then, I had to fold over and pull the dress over my head to just about manage to take it off. But it was worth it! Or so I thought. I felt like a flower wearing them, or an intricately decorated ikebana. Not being able to take a full breath was a small sacrifice for the enormous boost of glamourousness they gave me.

Of course, fitting into a dress meant no hearty dinners allowed. My waist needed to stay 58 cm, otherwise the dress would burst. Once, after an epic dinner that my friend organised at a Mediterranean restaurant, I had to miss dancing and excuse myself, going home with a violent stomachache after sucking my belly the whole evening.

Two decades later, after two babies and a biomechanics degree, my clothing choices are very different. I do still care about looking good in my clothes, but I take into account tissue mechanics and intraabdominal pressure when choosing my outfits too.

As you know, the standard clothing sizes have fixed measurements. Let’s say, UK size 10, EU 38, is tailored to fit a 70 cm waist. But did you know that the volumes of our abdominal and pelvic organs oscillate with food and water intake and throughout the menstrual cycle, affecting the waist size?

Our stomachs can expand quite a bit. The capacity of an average human stomach varies between 0.25 and about 1.7 litres after food (Ferrua, 2010). It’s not just the food volume, but also the gastric gas that adds up to the total volume. After large meals, the waist circumference can temporarily go up by 1-3 cm, even more in people with food intolerances or irritable bowel syndrome. Our viscera changes in volume too. Our small and large intestines oscillate from roughly 0.5 – 1 litres, varying throughout the day. The bladder, when full, can hold up to 400 ml of liquid, which also adds up.

Also, the menstrual cycle affects our waist circumference. Several studies found that the women’s waist circumference can increase by up to 2 cm in the late luteal (premenstrual) phase. One reason is the increase in the volume of the organs, and the other, water retention that increases and peaks at the onset of menstrual bleeding (White, 2011).

Huh! When we add that all up, our waists might go up and down by a whole clothing size, or even more, especially after multiple pregnancies, where the connective tissue across the front of the belly is stretched and the gap between the abdominal muscles is larger (Balasch – Bernat, 2021).

Why do we see slim waists as beautiful?

Because it’s so hard to achieve one. The consumerist society, with its abundance of processed food favours slim, narrow-waisted female silhouettes. The same as the prehistoric civilisations, with their lack of reliable food sources, idealised a female figure with folding layers of fat. Remember the Paleolithic fertility goddess sculpture Venus of Willendorf? She would have probably looked very different had they had a McDonald’s just around the corner from the cave.

Paleolithic venus figurines vs. a modern woman

“Venus of Dolní Věstonice” by Petr Novák, Wikipedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

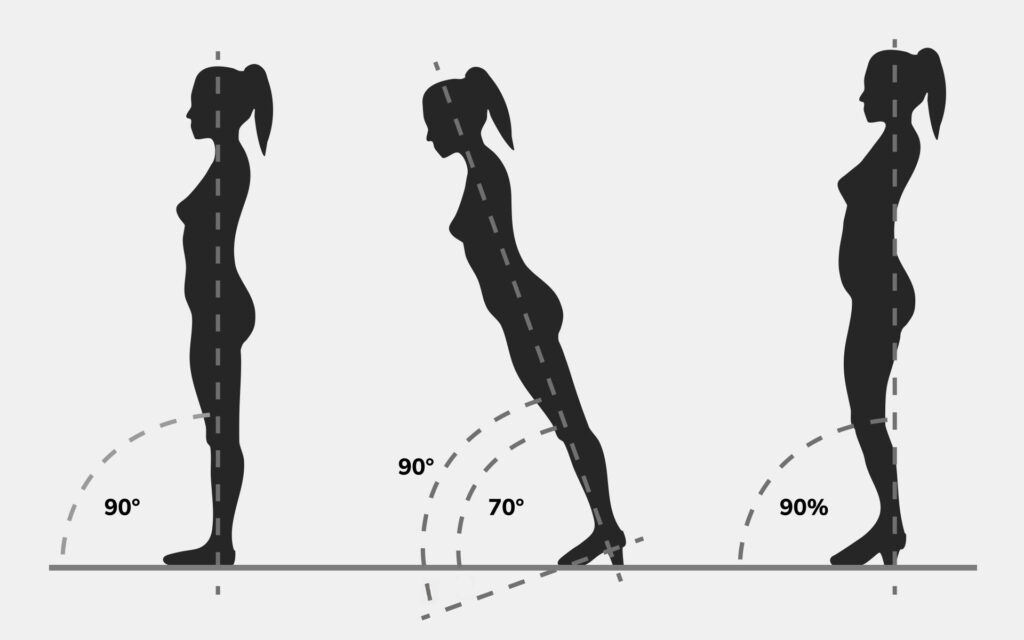

There are so many ways in which our culture and societal expectations have been shaping our bodies. Looking at shop windows the other day I noticed that most feminine tops and dresses seemed to show the breasts as higher than their anatomical placement. So, the women need to thrust their ribcage forward and up, pulling the thoracic spine along, to shape themselves into this unrealistic shape. This, seemingly subtle, postural adjustment profoundly changes the way the torso muscles work.

If you imagine your ribcage and the pelvis as two bowls of soup, the muscles attached to them would work the most efficiently if we place the two bowls directly on top of each other, aligning their centres of mass. This way, the postural muscles are within the optimum range of lengths to fully fire, supporting the spine.

But looking at the image above, you can see that the ribcage bowl is spilling soup down the back, while the pelvis bowl is spilling soup down the legs. This means, the abdominal muscles are stuck at being too long and back muscles too short to generate an effective muscle contraction. So, they are less effective at stabilizing the spine.

Also, deeper in the torso, the diaphragm and the pelvic floor, that anatomically sit on top of each other, are now in a position where they can’t work together effectively, so you might feel breathless, or leak when you sneeze or cough.

And what about the ideal of long-legs in high-heeled shoes? Where do high heels come from? How did we get to find them attractive?

There seem to be some parallels between high heels and the ancient Chinese practice of foot binding. Don’t you think that the foot below looks a bit like a high-heeled shoe?

The custom of foot binding was widely spread in China from around the 10th to early 20th century, especially amongst wealthy families. Starting from a very early age (3–4 years old) feet of young girls would gradually get deformed into the shape of a pointed lotus flower. Having bound feet was considered very attractive at the time and a prerequisite to a good marriage. Foot binding made walking extremely painful and women were physically impeded from moving about freely, which is in many ways similar to walking in extremely high heels.

Similarly to foot binding, high heels change how gravity affects the body and the muscles’ response to gravity.

In the short term, it’s much harder to just stay upright.

Illustration based on a concept by Erik Dalton, recreated for editorial use. Original source: erikdalton.com.

You can see on the graphic above how raising the heel decreases the angle between the lower leg and the ground, so the whole body leans forward. This means that you need to readjust the position of your knees, pelvis and the lower back and contract more muscles to stay upright (Lee, 2001). The higher the heel, the more extreme the compensations.

In the long term, our calf muscles shorten. A study published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology in 2015 found that increasing heel height from none to 13 cm, in healthy women, shortened their calf muscles (gastrocnemius) by at least 5% (Zöllnera, 2015). The body adapted by removing some sarcomeres — the basic contractile units within the fibres. The shortened calf muscles change how the ankle, knee and hip joints work together and affect function of seemingly unrelated areas (Csapo, 2010), from lower back, to the pelvic floor and even neck muscles.

Yes, you can still say that heels make you feel powerful, some women I know do. But, I think it’s important to have enough information when making our choices.

Back to my story.

It wasn’t until my first pregnancy that I discovered the joy of wearing comfortable clothes. Wow! What a difference! I refused to take them off for a year after. And then I got pregnant again. After the two close-up pregnancies, I was left with a 6-finger-width gap in the connective tissue across the front of my belly that took years to heal. Even after restoring my core strength post-pregnancies, and building abs, the connective tissue never fully came back together. This meant that when my stomach would get upset or slightly bloated, I would need a much larger top than my usual UK size 10.

So, I ditched all my narrow-waisted clothes, off to a charity shop! But then, I realised that I still do enjoy wearing fitted dresses sometimes. So, nowadays, I’ve found a compromise – I buy clothes with stretchy waists that look feminine, but allow me to breathe, move and have a large meal, if I feel like it.

Here is my personal checklist for clothes fitting, as a biomechanist, fashion-conscious woman and a mum. Feel free to borrow it!

- Can I move in this? — Can I take a deep breath, generously expanding the ribcage? Can I stretch my arms overhead? Fold forward? Squat? Did the fabric cut into my skin or restrict the movement?

- Would this still fit me after a big meal or during my period? — Does the waistline leave space for the natural changes in the volume of my organs as I eat and drink and get bloated before the menstruation?

- Do I feel good wearing this? — Is the fabric pleasant on my skin? Does the cut make me feel insecure or awkward? Do I feel I can be myself, at ease and relaxed wearing it?

What if a piece of clothing does not meet the three criteria above? Yes, of course, you can still wear it, but be aware that it is your choice and not anyone’s else. Wearing high heels sometimes and for a limited amount of time is OK. It’s a lifetime that matters.

Women are not made of plastic, we need to honour our bodies and all the physiological processes happening inside them! We want clothes to fit us, not having to mould our bodies to their shape.

The more we make conscious choices about what we wear and prioritise both aesthetics and comfort, the more women’s clothing trends will change to follow our tastes. Long live dresses with pockets!

References :

Balasch-Bernat, M., Pérez-Alenda, S., Carrasco, J. J., Valls-Donderis, B., Dueñas, L., & Fuentes-Aparicio, L. (2021). Differences in inter-rectus distance and abdominopelvic function between nulliparous, primiparous and multiparous women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), Article 12396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312396

Berg, E. E. (1995). Chinese foot binding. Orthopaedic Nursing, 14(5), 66-69.

Csapo, R., Maganaris, C. N., Seynnes, O. R., & Narici, M. V. (2010). On muscle, tendon and high heels. Journal of Experimental Biology, 213(15), 2582-2588. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.044271

Cummings, S. R., Ling, X., & Stone, K. (1997). Consequences of foot binding among older women in Beijing, China. American Journal of Public Health, 87(10), 1677-1679. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.87.10.1677

Ferrua, M. J., & Singh, R. P. (2010). Modeling the fluid dynamics in a human stomach to gain insight of food digestion. Journal of Food Science, 75(7), R151-R162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01748.x

Lee, C. M., Jeong, E. H., & Freivalds, A. (2001). Biomechanical effects of wearing high-heeled shoes. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 28(6), 321-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8141(01)00040-3

White, C. P., Hitchcock, C. L., Vigna, Y. M., & Prior, J. C. (2011). Fluid retention over the menstrual cycle: 1-year data from the prospective ovulation cohort. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2011, Article 138451. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/138451

Zöllner, A. M., Pok, J. M., McWalter, E. J., Gold, G. E., & Kuhl, E. (2015). On high heels and short muscles: A multiscale model for sarcomere loss in the gastrocnemius muscle. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 365, 301-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.10.036

Did you like this article?

Meet the Author

Ivana Demmel is a biomechanics scientist and back pain to performance specialist, passionate about women’s performance – both biological and athletic. Along her journey of overcoming chronic back pain and severe abdominal separation after two close-up pregnancies, Ivana transformed her personal fight into a professional challenge. Through 14 years of learning across the fields of movement and exercise science, physiotherapy and women’s health, and coaching many women stuck in the cracks of an exercise culture that doesn’t understand or prioritize women’s needs, she created her signature method rePower. At 45, she doesn’t suffer with back pain, lifts weights, and is the strongest she has ever been. “I’m committed to raising awareness about women’s unique needs and improving the standard of health and fitness support for active women, especially through postpartum recovery and menopausal transition.” You can find her on Instagram as @movementkitchen.